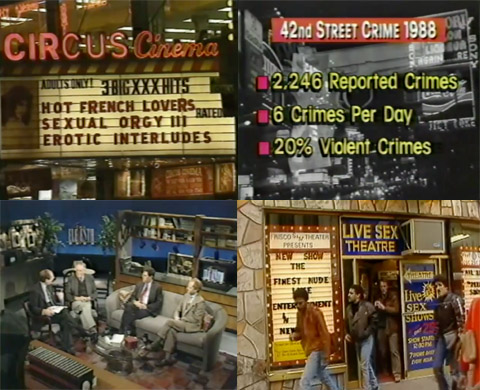

If you want to know why I decided to self-publish THE TUMOR, here are a few good reasons. A sampling of rejections of various short stories I submitted in recent years to publications ranging from the well-known to the deeply shitty. I can't even believe I submitted to some of these places. In fact, I can't believe I submitted to any of these places. Reasons for their decline are mostly generic, but my favorite is: "I think it's a little too graphic for us to run." Fanfuckingtastic. As Groucho Marx famously said: "PLEASE ACCEPT MY RESIGNATION. I DON'T WANT TO BELONG TO ANY CLUB THAT WILL ACCEPT PEOPLE LIKE ME AS A MEMBER." Support my work so I don't have continue getting rejected by these fucking morons, and you can enjoy reading awesome work like THE TUMOR, which you can buy online HERE today.

American Short Fiction: "We read your submission carefully and regret that we are unable to use it at this time. While the volume of submissions prevents us from responding specifically to your work, we wish you the best of luck in placing it elsewhere."

New England Review: "Thank you for giving us the chance to read [redacted]. While in the end we have decided against publishing this piece in the New England Review, we thought the writing had merit, and we wish you the best in placing it elsewhere."

Boulevard: "Thank you very much for sending [redacted] to Boulevard. We're sorry for taking such a long time with your work. Although it doesn't fill our editorial needs at the moment, we're glad you thought of us. Good luck placing this with another magazine."

Tin House: "Thank you for sending us [redacted]. Thank you, also, for your patience in waiting to hear back from us. Unfortunately, we must pass at this time. Best of luck placing your work elsewhere."

McSweeney's: "Thank you for sending us [redacted]. We rely on submissions like yours, since a good portion of what we publish comes to us unsolicited. Unfortunately, we can't find a place for this piece in our next few issues. But please feel free to submit again in the future. Our tastes and needs continuously change. Thanks again for your efforts, and for letting us see your work."

Guernica: "Thank you for submitting your short story to Guernica Magazine. It wasn't quite right for us, but we hope you will be able to place it elsewhere, and that you keep us in mind in the future. (If you do submit again, please do so in a new email thread: a reply to this message will get misfiled.)"

BOMB: "Thank you for your interest in BOMB Magazine. We appreciate your submission but regret to inform you that it does not meet our editorial needs at this time. We wish you luck placing your manuscript elsewhere. "

Metazen: "Thank you for letting us have a look at your work. While I've decided to pass on this one, I wish you much success in placing it elsewhere."

Failbetter: "Thanks for sharing your work with failbetter.com. We're sorry to report that it's not quite right for our site. We apologize for the delay in responding, and wish you the best of luck in placing it elsewhere."

The Toast: "I think it's a little too graphic for us to run, but thanks for letting us have a look! We're always open to pitches."

Digital Americana Magazine: "Thank you for submitting your work to us for the Fall 2013 issue. We appreciate the chance to read it. Unfortunately, we were not able to find a place for your piece in this issue. Thanks again. Best of luck with future submissions."

Juked: "Thank you for sending us your work. We appreciated the read, but we're sorry to say we are unable to use this submission. We wish you the best on finding a good home for this piece."

Birkensnake: "Thank you for letting us see [redacted]. We're going to pass on it, but we enjoyed it more than is usual, and we look forward to reading more of your work one day."

High Desert Journal: "Thank you for sending us [redacted]. We appreciate the chance to read it. Unfortunately, the piece is not for us."

AGNI: "Thank you for sending [redacted]. Your work received careful consideration here. We've decided this manuscript isn't right for us, but we wish you luck placing it elsewhere."

The Threepenny Review: "We have read your submission, and unfortunately we are not able to use it in The Threepenny Review. Please do not take this as a comment on the quality of your writing; we receive so many submissions that we are able to accept only a small fraction of them."

Buy THE TUMOR: "This is one of the weirdest, smartest, most disturbing things you will read this year."