Data Baby Dedication

The dedication for my memoir, Data Baby: My Life in a Psychological Experiment, via X’s @dedication_bot.

About I My Book | Consulting I X I Instagram I LinkedIn I Email

The dedication for my memoir, Data Baby: My Life in a Psychological Experiment, via X’s @dedication_bot.

About I My Book | Consulting I X I Instagram I LinkedIn I Email

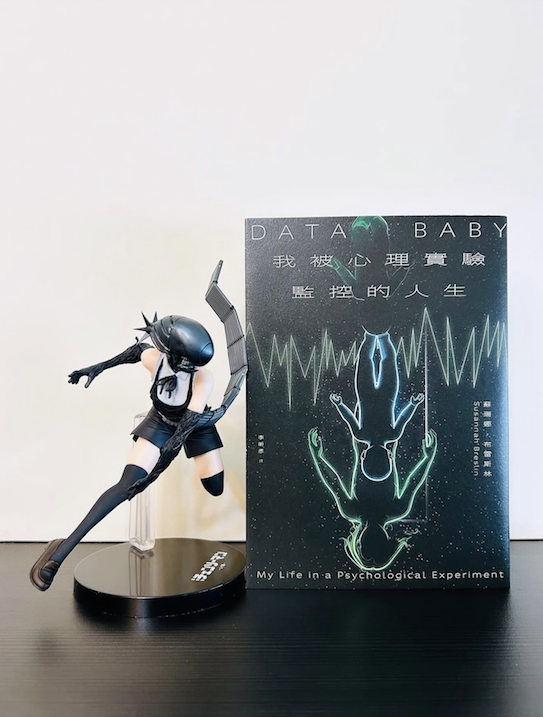

Thank you to @whenifree_iread for posting this cool photo of the Taiwanese edition of my memoir, Data Baby.

About I My Book | Consulting I X I Instagram I LinkedIn I Email

I’m eager to read this new book by the late photographer Larry Sultan: Water Over Thunder: Selected Writings.

About I My Book | Consulting I X I Instagram I LinkedIn I Email

Last year I read Atomic Habits by James Clear, which I found to be relatively helpful in habit building. This year I read the companion workbook, which I found to be less helpful. It feels underdeveloped. So maybe skip it.

About I My Book | Consulting I X I Instagram I LinkedIn I Email

What if your parents turn you into a human lab rat when you’re a child? Will that change the story of your life? Will that change who you are? Find out in my memoir: Data Baby: My Life in a Psychological Experiment.

About I My Book | Consulting I X I Instagram I LinkedIn I Email

Roadside Picnic by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky is a curious book. There is a monkey child, a zone where terrible things happen, a “stalker” who is hunting for … what? Money? Hope? Dreams? This book was the inspiration for Stalker, which you should watch if you haven’t. But truth be told: The book is better.

About I My Book | Consulting I X I Instagram I LinkedIn I Email

“Fascinating. […] Unpacking thorny questions about determinism and the ethics of human experimentation, Breslin attacks her subject with verve and wit, resisting woe-is-me solipsism without defanging her critiques of the study that rocked her life. It’s gripping stuff.” — buy Data Baby: My Life in a Psychological Experiment

About | Consulting I My Book I X I Instagram I LinkedIn I Email

I first read William Blake’s Songs of Innocence and Experience in college. I highly recommend this small version.

About | Consulting I My Book I X I Instagram I LinkedIn I Email

I’m happy to share I’m one of the judges of the 2026 Tournament of Books. Follow along and learn more here.

About | Consulting I My Book I X I Instagram I LinkedIn I Email

Two years ago, I published my memoir, Data Baby: My Life in a Psychological Experiment. In a starred review, Publishers Weekly deemed it “gripping.” Kirkus Reviews called it “An intelligently provocative memoir and investigation.” The Globe and Mail named it “thought-provoking, ridiculously propulsive.” Read about it.

About | Consulting I Email

The front-of-the-book dedication of my investigative memoir, Data Baby: My Life in a Psychological Experiment.

About I My Book I Newsletter I X I Instagram I LinkedIn I Consulting I Email

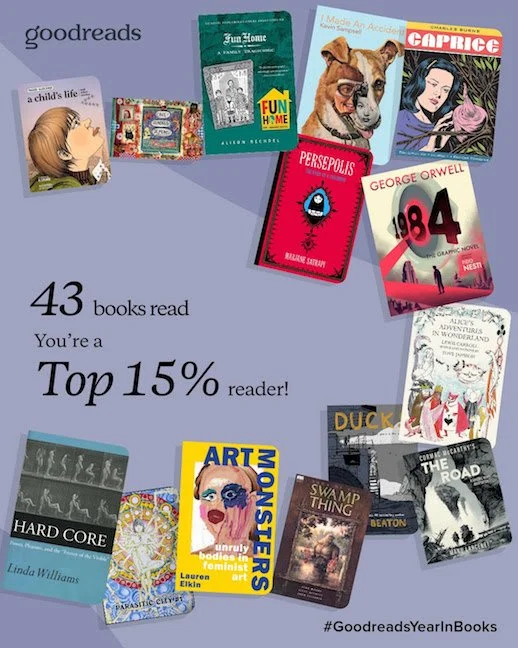

Linda Williams’ Hard Core: Power, Pleasure, and the “Frenzy of the Visible” is a rigorously academic work that seeks to trace the history of pornographic movies and explore what their content reveals about their viewers. Dense and filled with academese, the book tackles adult content with all the sexiness of a spatula. While not strictly feminist, Williams’ work privileges feminist porn over not-feminist porn while failing to identify if there is an actual difference between the two beyond an ultimately failed marketing ploy. This book is a buzzkill.

About I My Book I Newsletter I X I Instagram I LinkedIn I Consulting I Email

This is part 26 of Fuck You, Pay Me, an ongoing series of posts on writing, editing, and publishing.

I’m happy to announce that my memoir, Data Baby: My Life in a Psychological Experiment, has been translated into Mandarin and published in Taiwan by Akker Publishing. I love the haunting and sci-fi-ish new cover.

Data Baby recounts my 30-year tenure, from early childhood and well into adulthood, as a research subject in a pioneering University of California, Berkeley longitudinal study of personality development that sought to predict who a cohort of over 100 Berkeley kids, including me, would grow up to be.

Actress Emma Roberts’ Belletrist book club selected Data Baby as its December 2023 pick. In a starred review, Publishers Weekly called it “a fascinating debut memoir” and “gripping stuff.” Kirkus Reviews deemed it “An intelligently provocative memoir and investigation.” And The Globe and Mail described it as “a thought-provoking, ridiculously propulsive book.” I also wrote an essay about what it’s like to be a child guinea pig for Slate. Learn more about my book here.

About I My Book I Newsletter I X I Instagram I LinkedIn I Consulting I Email

Revisiting “I Spent My Childhood as a Guinea Pig for Science. It Was … Great?”—my personal essay, on Slate.

About I My Book I Newsletter I X I Instagram I LinkedIn I Consulting I Email