Starlite Terrace

Doing research for my novel set in the adult movie industry, I checked out Starlite Terrace in Sherman Oaks.

About I My Book I Newsletter I X I Instagram I LinkedIn I Consulting I Email

Doing research for my novel set in the adult movie industry, I checked out Starlite Terrace in Sherman Oaks.

About I My Book I Newsletter I X I Instagram I LinkedIn I Consulting I Email

Image credit: Nikola Tamindzic

Research shows that people who subscribe to my newsletter have more and better sex than people who don’t.

About I My Book I Newsletter I X I Instagram I LinkedIn I Consulting I Email

Follow me on Threads here.

About I My Book I Newsletter I X I Instagram I LinkedIn I Consulting I Email

This past spring, I wrote an opinion essay about children and privacy. The essay was inspired by and informed by my memoir, Data Baby: My Life in a Psychological Experiment, in which I detailed how being a research subject from childhood to adulthood shaped me and changed the trajectory of my life. I submitted the essay to various outlets, but no one was interested in publishing it, so I’m publishing it here for the first time.

Today’s kids grow up online. From the first sonogram image posted to a parent’s Facebook profile to providing toddler content fodder for a mommy influencer’s TikTok account, Gen Z has never known what it is to have a private life. Without their knowledge or consent the most intimate moments of these children’s lives, embarrassing meltdowns and potty training scenes alike, have been shared, scrutinized, and commented upon by people they will never meet.

I know something of what it’s like to grow up without a sense of privacy. Not long after I was born, in the spring of 1968, my parents submitted an application for my enrollment in an exclusive “laboratory preschool” run by the University of California, Berkeley, where my father was a poetry professor. When I arrived at the Harold E. Jones Child Study Center for my first day of nursery school, I became one of over 100 Berkeley children in a groundbreaking, 30-year longitudinal study of personality that sought to answer a question: If you study a child, can you predict who that child will grow up to be?

Over three decades, my cohort and I were studied extensively. At the preschool, which had been designed for spying on children, researchers observed us from a hidden observation gallery overlooking the classroom and assessed us in testing rooms equipped with one-way mirrors and eavesdropping devices. After preschool, the cohort scattered to the winds, but our principal investigators continued following us. At Tolman Hall, a Brutalist building on the north side of campus that housed the Department of Psychology, we were evaluated at key development stages. Our school report cards were analyzed. Our parents were interviewed. We were studied at home and in an RV that had been turned into a mobile laboratory with a hidden compartment in the rear from which one researcher looked on as another researcher evaluated us.

In the early years, I didn’t know I was being studied. Eventually, I learned I was part of an important study. In the beginning, my parents consented for me. When I got older, I consented for myself. I liked being studied. At home, my English professor parents were preoccupied with work, and I spent a lot of time alone in my room entertaining myself. In an experiment room, I was the center of attention. My intellectual parents were emotionally distant. The close attention paid to me by a researcher sitting across the table from me felt a lot like love.

From its first chapter, my life was an open book. As I understood it, my private life was not my own but something to be offered up willingly to science in service of enlightening humanity. In my mind, being a human lab rat was my destiny. Over time, our lives would inform over 100 books and scientific papers. The study would shed new light on how people become who they are, report that adult political orientation can be predicted from toddlerhood, and prove that, to some degree, you can foresee who a child will grow up to be.

According to the observer effect, the act of observation changes that which is being observed. Without a doubt, being studied changed my life. It made me feel like I mattered when my parents didn’t; its researchers’ keen interest in my life story played a role in shaping me into the writer I would become. When I was in my early thirties, the study ended, and in hindsight I can see I felt a bit lost without it. Who was I without my overseers watching over me?

I think about my experiences as a research subject when I think about Gen Z, the pioneering generation that is coming of age publicly. They are unwitting research subjects in a global-scale psychological experiment, one in which they are human guinea pigs and the unanswered question is: How will growing up in the public eye shape their identities? After all, this generation’s overseers are not kindly researchers who want to understand human nature but Big Tech billionaires who have fine-tuned their algorithms to not simply study their youngest users but to guide their choices, mold their senses of self, steer their minds.

According to a 2023 Gallup survey, the average American teenager spends 4.8 hours a day on social media. In January, Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg engaged in senatorial theater, suggesting the company was undertaking steps to reduce the potential for harms caused by social media on teens. In his State of the Union Address in March, President Joe Biden made a brief reference to his goal to “Pass bipartisan privacy legislation to protect our children online.”

For kids, it may be too late to save what they’ve lost already: a private life.

About | My Book I Newsletter I X I Instagram I LinkedIn I Consulting I Email

This is an excerpt from my memoir, Data Baby: My Life in a Psychological Experiment. You can order a copy here.

Image via Wikipedia

I thought it would be interesting to write about the strip clubs in the North Beach neighborhood of San Francisco. I was curious about these enigmatic clubs on Broadway that I had seen but into which I had never entered. As a kid in the back seat of my parents’ Dart, I had been driven through San Francisco and spotted The Condor (which, in 1964, had become the country’s first fully topless nightclub). Out front, a towering sign featured a supersized blonde, impossibly busty. Her name, I would find out later, was Carol Doda. She wore a black bikini with blinking red lights for nipples.

Doda was the opposite of my mother and her friends—they were feminists who viewed makeup, heavily styled hair, and revealing clothes as tools the patriarchy used to subjugate and objectify women. But Doda wasn’t anyone’s tool; she was a legend. A San Francisco Art Institute dropout, she had become America’s first topless dancer of note, her surgically enhanced breasts billed as “the new Twin Peaks of San Francisco.” When I was in graduate school, I had seen an episode of HBO’s “Real Sex” about strippers, and I had been struck by the revelation that strip clubs were places where intimacy was for sale. Sure, it was transient, transactional, and most often conducted between a guy with a handful of dollar bills and a dancer in a G-string and not much else who twirled seductively around a pole on a stage, but there was something real about it, I sensed. Or was there? I wanted to find out. The strip club dancers reminded me of the girls I had hung out with in high school, whom everyone else had deemed slutty. These women were powerful, too, in control, the love object I aspired to be, or seemed like it. Intimacy, that for which I had craved as a little girl, was their hustle.

“Oh, my god, Susannah, make up your mind!” Anne laughed as we stood at the corner on a Saturday night. Broadway was teeming with drunk guys, sailors on leave, and couples on the prowl for something more interesting than what they had already. I scanned the glowing signs. Roaring 20’s. Big Al’s. The Hungry I.

“This one!”

We ducked inside.

As we moved down the black hallway toward a red velvet curtain, I worried what someone else in the club might think. I, a woman, was in a strip club. As I pulled back the curtain, it dawned on me that wasn’t going to be an issue. There was one thing to which the men scattered at the small dimly lit tables around the room were paying attention, and it wasn’t me. It was the half-naked girl on the stage.

Nonchalantly, we took a seat at a table near the back. We ordered a couple of overpriced drinks. I took a sip: it was straight orange juice. The cocktails were alcohol-free, thanks to a California law that prohibited the sale of alcohol in fully nude strip clubs. It didn’t matter, my head was buzzing from the drinks we’d had at the bar around the corner that we’d been to earlier.

In the song that was blasting, Trent Reznor was expressing a desire to violate someone. The statuesque brunette teetering on the highest heels I had ever seen peeled off her dental-floss thin neon green thong. She tossed her thong to one side, grabbed the pole, climbed up it. High above the crowd, she wrapped her thighs around the pole and bent over backwards, throwing her arms open like an inverted angel.

In that moment, everything that had happened seemed far away. The intellectual, cloistered, academic world in which I had grown up was right across the Bay, but it may as well have been a million miles from here. I looked at a solitary businessman sitting at the next table. His tie was untied. His jacket was slung across the back of his chair. His eyes were glassy. He had been hypnotized. In this alternative universe, women had all the power, and men were at their mercy. I didn’t want to be a stripper; I was too shy, too insecure, too inhibited to take off my clothes in front of strangers. But I wanted what she had: the stage, the men in awe, the audience worshipping her as a superhuman goddess. As a kid, I was starved for attention. This was an orgy of attention. As a pre-pubescent girl, I felt embarrassed by my own burgeoning sexuality, left to figure it out for myself because my mother was too depressed. Here, sex was on parade, for sale, everywhere I looked. In the Block Project, I was the object, the one on view, the child studied by researchers from across tables in Tolman Hall’s austere experiment rooms. Now I was the voyeur, the looker, the scopophiliac. It was intoxicating.

As we sped back to the East Bay in the early morning hours, I watched the city get smaller and smaller in the side view mirror. My father was dead, that was an incontrovertible fact, but for a few hours tonight I had forgotten all about that. I could write about this. I could become a gonzo journalist, like one of my favorite writers, Hunter S. Thompson, and immerse myself in it. Sex would be my beat.

About | My Book I Newsletter I X I Instagram I LinkedIn I Consulting I Email

In a previous post that I titled “The Porn Library,” I shared a list of books about the adult movie industry. After I posted it, I started thinking about how there are other works about the porn industry in other mediums: like, for example, movies, TV shows, and art. So I created The Porn Library. Basically, it’s a compendium of works about the adult movie business. That includes books like Pornocopia: Porn, Sex, Technology and Desire by Laurence O’Toole, movies like 8mm directed by Joel Schumacher, journalism like my own “They Shoot Porn Stars, Don’t They?”, podcasts like The Last Days of August by Jon Ronson, and artworks like 003.jpg by Adam Connelly. Aware of something that I’m missing? You can share your suggestions with me here.

Buy My Book I About | Blog I Newsletter I X I Instagram I LinkedIn I Hire Me I Email

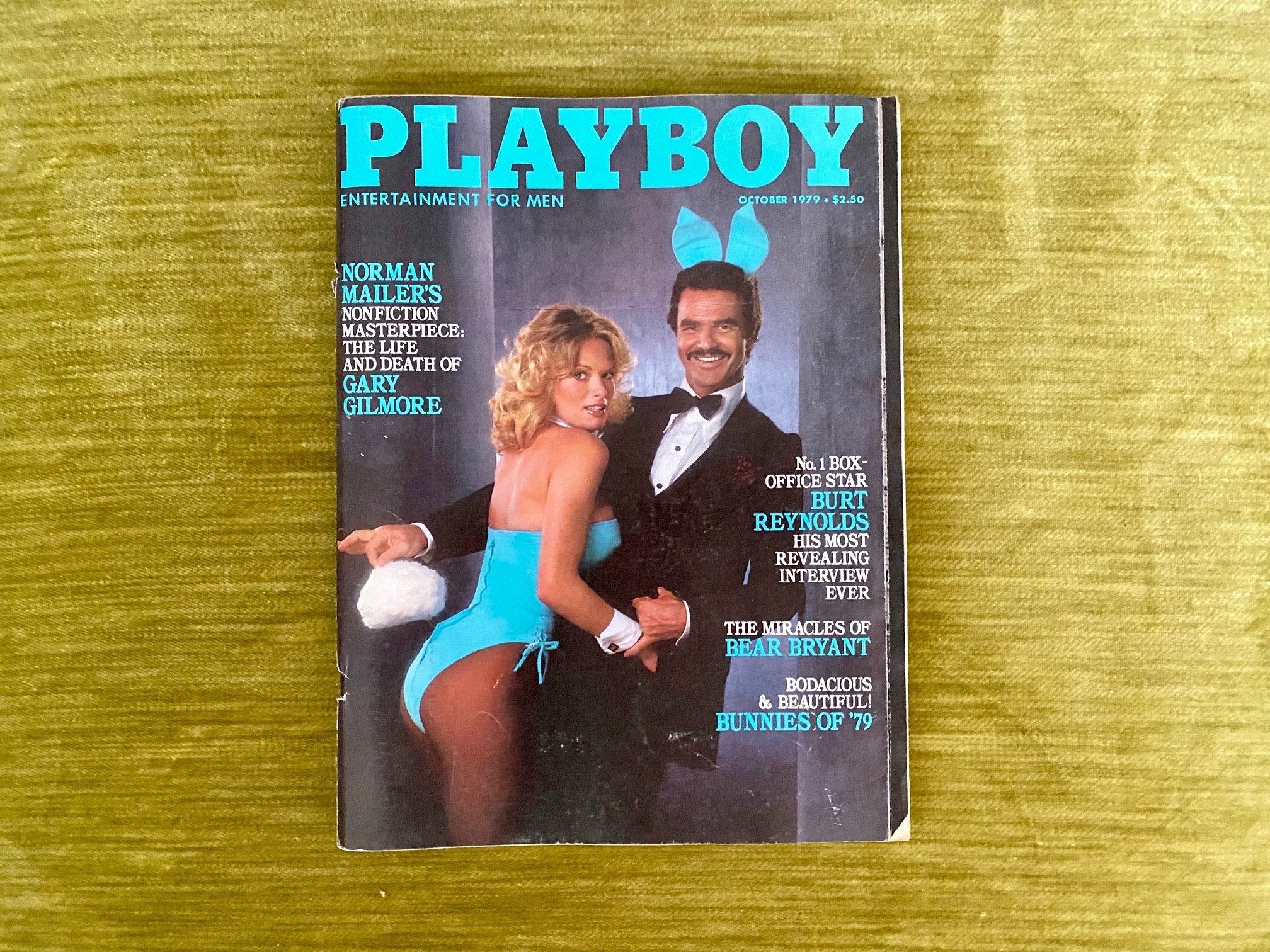

I bought this Playboy the other day at a vintage store in Atwater Village on the east side of Los Angeles. I had been planning on mentioning this very issue (October 1979) in the novel I’m working on, which I refer to as “The Porn Novel,” and so when I saw it there, on the table, I thought it was a sign. What kind of sign? Who knows. Sometimes you just need to go with them. Anyway, I paid $15 for it, which is a little steep, because I probably could’ve got it online for a little less, or maybe not, who cares. Anyway, I tweeted about it after I bought it, saying that touching this used copy had gotten me pregnant, which was a joke, of course.

Buy My Book | Hire Me | About | Blog | Forbes | Twitter | Instagram | LinkedIn | Email

What if every memory you ever had ended up in a file in your head? Would you be a cathedral? Or a filing cabinet? A great scene from “Doctor Sleep.”

Like what I do? Support my work! Buy my digital short story: THE TUMOR.

Research. pic.twitter.com/4fTvPvBxGP

— Susannah Breslin (@susannahbreslin) April 1, 2014